---

title: "Quantum gate"

firstLetter: "Q"

publishDate: 2021-03-29

categories:

- Quantum information

date: 2021-03-29T21:37:57+02:00

draft: false

markup: pandoc

---

# Quantum gate

In quantum computing, **quantum gates** are the equivalent

of classical binary logic gates such as $\mathrm{NOT}$, $\mathrm{AND}$, etc.

Because of the continuous nature of qubits,

the number of possible quantum gates is uncountably infinite,

so we only consider the most important examples here.

## One-qubit gates

As an example, consider the following must general single-qubit state $\ket{\psi}$:

$$\begin{aligned}

\ket{\psi}

= \alpha \ket{0} + \beta \ket{1}

= \begin{bmatrix} \alpha \\ \beta \end{bmatrix}

\end{aligned}$$

Arguably the most famous and/or most fundamental quantum gates are the **Pauli matrices**:

$$\begin{aligned}

\boxed{

X =

\begin{bmatrix}

0 & 1 \\

1 & 0

\end{bmatrix}

}

\qquad

\boxed{

Y =

\begin{bmatrix}

0 & -i \\

i & 0

\end{bmatrix}

}

\qquad

\boxed{

Z =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 \\

0 & -1

\end{bmatrix}

}

\end{aligned}$$

They have the following effect on $\ket{\psi}$.

Note that $X$ is equivalent to the classical $\mathrm{NOT}$ gate

(and is often given that name),

and $Z$ is sometimes called the **phase-flip gate**:

$$\begin{aligned}

X \ket{\psi}

= \begin{bmatrix} \beta \\ \alpha \end{bmatrix}

\qquad

Y \ket{\psi}

= \begin{bmatrix} -i \beta \\ i \alpha \end{bmatrix}

\qquad

Z \ket{\psi}

= \begin{bmatrix} \alpha \\ -\beta \end{bmatrix}

\end{aligned}$$

In fact, $Z$ is a specific case of the **phase shift gate** $R_\phi$,

which modifies the qubit's phase without changing its amplitudes.

For an angle $\phi$, it is given by:

$$\begin{aligned}

\boxed{

R_\phi =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 \\

0 & e^{i \phi}

\end{bmatrix}

}

\end{aligned}$$

For $\phi = \pi$, we recover the Pauli-$Z$ gate.

In general, the action of $R_\phi$ is as follows:

$$\begin{aligned}

R_\phi \ket{\psi}

= \begin{bmatrix} \alpha \\ e^{i \phi} \beta \end{bmatrix}

\end{aligned}$$

Two common special cases of $R_\phi$

are $\phi = \pi/2$ and $\phi = \pi/4$,

respectively called $S$ and $T$:

$$\begin{aligned}

\boxed{

S = R_{\pi/2} =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 \\

0 & i

\end{bmatrix}

}

\qquad \quad

\boxed{

T = R_{\pi/4} =

\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}

\begin{bmatrix}

\sqrt{2} & 0 \\

0 & 1 + i

\end{bmatrix}

}

\end{aligned}$$

Finally, we have the **Hadamard gate** $H$,

which is defined as follows:

$$\begin{aligned}

\boxed{

H = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 1 \\

1 & -1

\end{bmatrix}

}

\end{aligned}$$

Its action consists of rotating the qubit

by $\pi$ around the axis $(X + Z) / \sqrt{2}$ of the Bloch sphere:

$$\begin{aligned}

H \ket{\psi}

= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \begin{bmatrix} \alpha + \beta \\ \alpha - \beta \end{bmatrix}

\end{aligned}$$

Notably, it maps the eigenstates of $X$ and $Z$ to each other,

and is its own inverse (i.e. unitary):

$$\begin{aligned}

H \ket{0} = \ket{+}

\qquad

H \ket{1} = \ket{-}

\qquad

H \ket{+} = \ket{0}

\qquad

H \ket{-} = \ket{1}

\end{aligned}$$

The **Clifford gates** are a set including $X$, $Y$, $Z$, $H$ and $S$,

or more generally any gates that rotate

by multiples of $\pi/2$ around the Bloch sphere.

This set is **not universal**, meaning that if we start from $\ket{0}$,

we can only reach $\ket{0}$, $\ket{1}$, $\ket{+}$, $\ket{-}$, $\ket{+i}$ $\ket{-i}$ using these gates.

If we add *any* non-Clifford gate, for example $T$,

then we can reach any point on the Bloch sphere,

which means that the set is **universal**.

However, there is a problem: a qubit has an uncountable infinity of states,

but a quantum circuit consists of a countably infinite sequence of gates, at most.

Therefore, technically, we can never reach the whole Bloch sphere,

but we *can* come up with circuits that approximate a target state to some degree $\varepsilon$.

This is the definition of universality:

any state can be approximated.

## Two-qubit gates

As an example, let us consider

the following two pure one-qubit states $\ket{\psi_1}$ and $\ket{\psi_2}$:

$$\begin{aligned}

\ket{\psi_1}

= \alpha_1 \ket{0} + \beta_1 \ket{1}

= \begin{bmatrix} \alpha_1 \\ \beta_1 \end{bmatrix}

\qquad \quad

\ket{\psi_2}

= \alpha_2 \ket{0} + \beta_2 \ket{1}

= \begin{bmatrix} \alpha_2 \\ \beta_2 \end{bmatrix}

\end{aligned}$$

The composite state of both qubits, assuming they are pure,

is then their tensor product $\otimes$:

$$\begin{aligned}

\ket{\psi_1 \psi_2}

= \ket{\psi_1} \otimes \ket{\psi_2}

&= \alpha_1 \alpha_2 \ket{00} + \alpha_1 \beta_2 \ket{01} + \beta_1 \alpha_2 \ket{10} + \beta_1 \beta_2 \ket{11}

\\

&= c_{00} \ket{00} + c_{01} \ket{01} + c_{10} \ket{10} + c_{11} \ket{11}

\end{aligned}$$

Note that a two-qubit system may be [entangled](/know/concept/quantum-entanglement/),

in which case the coefficients $c_{00}$ etc. cannot be written as products,

i.e. $\ket{\psi_2}$ cannot be expressed separately from $\ket{\psi_1}$, and vice versa.

In other words, the general action of a two-qubit quantum gate

can be expressed in the basis of $\ket{00}$, $\ket{01}$, $\ket{10}$ and $\ket{11}$,

but not always in the basis of $\ket{0}_1$, $\ket{1}_1$, $\ket{0}_2$ and $\ket{1}_2$.

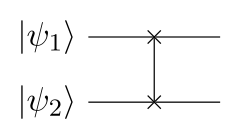

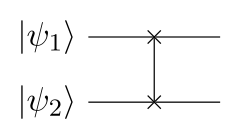

With that said, the first two-qubit gate is $\mathrm{SWAP}$,

which simply swaps $\ket{\psi_1}$ and $\ket{\psi_2}$:

$$\begin{aligned}

\boxed{

\mathrm{SWAP} =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

}

\end{aligned}$$

This matrix is given in the basis of $\ket{00}$, $\ket{01}$, $\ket{10}$ and $\ket{11}$.

Note that $\mathrm{SWAP}$ cannot generate entanglement,

so if its input is separable, its output is too.

In any case, its effect is clear:

$$\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{SWAP} \ket{\psi_1 \psi_2}

&= c_{00} \ket{00} + c_{10} \ket{01} + c_{01} \ket{10} + c_{11} \ket{11}

\end{aligned}$$

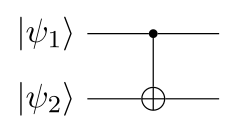

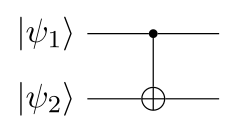

Next, there is the **controlled NOT gate** $\mathrm{CNOT}$,

which "flips" (applies $X$ to) $\ket{\psi_2}$ if $\ket{\psi_1}$ is true:

$$\begin{aligned}

\boxed{

\mathrm{SWAP} =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

}

\end{aligned}$$

This matrix is given in the basis of $\ket{00}$, $\ket{01}$, $\ket{10}$ and $\ket{11}$.

Note that $\mathrm{SWAP}$ cannot generate entanglement,

so if its input is separable, its output is too.

In any case, its effect is clear:

$$\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{SWAP} \ket{\psi_1 \psi_2}

&= c_{00} \ket{00} + c_{10} \ket{01} + c_{01} \ket{10} + c_{11} \ket{11}

\end{aligned}$$

Next, there is the **controlled NOT gate** $\mathrm{CNOT}$,

which "flips" (applies $X$ to) $\ket{\psi_2}$ if $\ket{\psi_1}$ is true:

$$\begin{aligned}

\boxed{

\mathrm{CNOT} =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0

\end{bmatrix}

}

\end{aligned}$$

That is, it swaps the last two coefficients $c_{10}$ and $c_{11}$ in the composite state vector:

$$\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{CNOT} \ket{\psi_1 \psi_2}

&= c_{00} \ket{00} + c_{01} \ket{01} + c_{11} \ket{10} + c_{10} \ket{11}

\end{aligned}$$

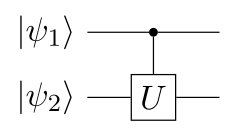

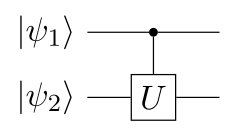

More generally, from every one-qubit gate $U$,

we can define a two-qubit **controlled U gate** $\mathrm{CU}$,

which applies $U$ to $\ket{\psi_2}$ if $\ket{\psi_1}$ is true:

$$\begin{aligned}

\boxed{

\mathrm{CNOT} =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0

\end{bmatrix}

}

\end{aligned}$$

That is, it swaps the last two coefficients $c_{10}$ and $c_{11}$ in the composite state vector:

$$\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{CNOT} \ket{\psi_1 \psi_2}

&= c_{00} \ket{00} + c_{01} \ket{01} + c_{11} \ket{10} + c_{10} \ket{11}

\end{aligned}$$

More generally, from every one-qubit gate $U$,

we can define a two-qubit **controlled U gate** $\mathrm{CU}$,

which applies $U$ to $\ket{\psi_2}$ if $\ket{\psi_1}$ is true:

$$\begin{aligned}

\boxed{

\mathrm{CU} =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & u_{00} & u_{01} \\

0 & 0 & u_{10} & u_{11}

\end{bmatrix}

}

\end{aligned}$$

Where the lower-right 2x2 block is simply $U$.

The general action of this gate is given by:

$$\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{CU} \ket{\psi_1 \psi_2}

&= c_{00} \ket{00} + c_{01} \ket{01} + (c_{10} u_{00} + c_{11} u_{01}) \ket{10} + (c_{10} u_{10} + c_{11} u_{11}) \ket{11}

\end{aligned}$$

A set of gates is **universal** if all possible mappings

from $n$ to $n$ qubits can be approximated using only these gates.

A minimal universal set is $\{\mathrm{CNOT}, T, S\}$,

and there exist many others.

## References

1. J.S. Neergaard-Nielsen,

*Quantum information: lectures notes*,

2021, unpublished.

2. S. Aaronson,

*Introduction to quantum information science: lecture notes*,

2018, unpublished.

$$\begin{aligned}

\boxed{

\mathrm{CU} =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & u_{00} & u_{01} \\

0 & 0 & u_{10} & u_{11}

\end{bmatrix}

}

\end{aligned}$$

Where the lower-right 2x2 block is simply $U$.

The general action of this gate is given by:

$$\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{CU} \ket{\psi_1 \psi_2}

&= c_{00} \ket{00} + c_{01} \ket{01} + (c_{10} u_{00} + c_{11} u_{01}) \ket{10} + (c_{10} u_{10} + c_{11} u_{11}) \ket{11}

\end{aligned}$$

A set of gates is **universal** if all possible mappings

from $n$ to $n$ qubits can be approximated using only these gates.

A minimal universal set is $\{\mathrm{CNOT}, T, S\}$,

and there exist many others.

## References

1. J.S. Neergaard-Nielsen,

*Quantum information: lectures notes*,

2021, unpublished.

2. S. Aaronson,

*Introduction to quantum information science: lecture notes*,

2018, unpublished.

$$\begin{aligned}

\boxed{

\mathrm{SWAP} =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

}

\end{aligned}$$

This matrix is given in the basis of $\ket{00}$, $\ket{01}$, $\ket{10}$ and $\ket{11}$.

Note that $\mathrm{SWAP}$ cannot generate entanglement,

so if its input is separable, its output is too.

In any case, its effect is clear:

$$\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{SWAP} \ket{\psi_1 \psi_2}

&= c_{00} \ket{00} + c_{10} \ket{01} + c_{01} \ket{10} + c_{11} \ket{11}

\end{aligned}$$

Next, there is the **controlled NOT gate** $\mathrm{CNOT}$,

which "flips" (applies $X$ to) $\ket{\psi_2}$ if $\ket{\psi_1}$ is true:

$$\begin{aligned}

\boxed{

\mathrm{SWAP} =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1

\end{bmatrix}

}

\end{aligned}$$

This matrix is given in the basis of $\ket{00}$, $\ket{01}$, $\ket{10}$ and $\ket{11}$.

Note that $\mathrm{SWAP}$ cannot generate entanglement,

so if its input is separable, its output is too.

In any case, its effect is clear:

$$\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{SWAP} \ket{\psi_1 \psi_2}

&= c_{00} \ket{00} + c_{10} \ket{01} + c_{01} \ket{10} + c_{11} \ket{11}

\end{aligned}$$

Next, there is the **controlled NOT gate** $\mathrm{CNOT}$,

which "flips" (applies $X$ to) $\ket{\psi_2}$ if $\ket{\psi_1}$ is true:

$$\begin{aligned}

\boxed{

\mathrm{CNOT} =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0

\end{bmatrix}

}

\end{aligned}$$

That is, it swaps the last two coefficients $c_{10}$ and $c_{11}$ in the composite state vector:

$$\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{CNOT} \ket{\psi_1 \psi_2}

&= c_{00} \ket{00} + c_{01} \ket{01} + c_{11} \ket{10} + c_{10} \ket{11}

\end{aligned}$$

More generally, from every one-qubit gate $U$,

we can define a two-qubit **controlled U gate** $\mathrm{CU}$,

which applies $U$ to $\ket{\psi_2}$ if $\ket{\psi_1}$ is true:

$$\begin{aligned}

\boxed{

\mathrm{CNOT} =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0

\end{bmatrix}

}

\end{aligned}$$

That is, it swaps the last two coefficients $c_{10}$ and $c_{11}$ in the composite state vector:

$$\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{CNOT} \ket{\psi_1 \psi_2}

&= c_{00} \ket{00} + c_{01} \ket{01} + c_{11} \ket{10} + c_{10} \ket{11}

\end{aligned}$$

More generally, from every one-qubit gate $U$,

we can define a two-qubit **controlled U gate** $\mathrm{CU}$,

which applies $U$ to $\ket{\psi_2}$ if $\ket{\psi_1}$ is true:

$$\begin{aligned}

\boxed{

\mathrm{CU} =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & u_{00} & u_{01} \\

0 & 0 & u_{10} & u_{11}

\end{bmatrix}

}

\end{aligned}$$

Where the lower-right 2x2 block is simply $U$.

The general action of this gate is given by:

$$\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{CU} \ket{\psi_1 \psi_2}

&= c_{00} \ket{00} + c_{01} \ket{01} + (c_{10} u_{00} + c_{11} u_{01}) \ket{10} + (c_{10} u_{10} + c_{11} u_{11}) \ket{11}

\end{aligned}$$

A set of gates is **universal** if all possible mappings

from $n$ to $n$ qubits can be approximated using only these gates.

A minimal universal set is $\{\mathrm{CNOT}, T, S\}$,

and there exist many others.

## References

1. J.S. Neergaard-Nielsen,

*Quantum information: lectures notes*,

2021, unpublished.

2. S. Aaronson,

*Introduction to quantum information science: lecture notes*,

2018, unpublished.

$$\begin{aligned}

\boxed{

\mathrm{CU} =

\begin{bmatrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & u_{00} & u_{01} \\

0 & 0 & u_{10} & u_{11}

\end{bmatrix}

}

\end{aligned}$$

Where the lower-right 2x2 block is simply $U$.

The general action of this gate is given by:

$$\begin{aligned}

\mathrm{CU} \ket{\psi_1 \psi_2}

&= c_{00} \ket{00} + c_{01} \ket{01} + (c_{10} u_{00} + c_{11} u_{01}) \ket{10} + (c_{10} u_{10} + c_{11} u_{11}) \ket{11}

\end{aligned}$$

A set of gates is **universal** if all possible mappings

from $n$ to $n$ qubits can be approximated using only these gates.

A minimal universal set is $\{\mathrm{CNOT}, T, S\}$,

and there exist many others.

## References

1. J.S. Neergaard-Nielsen,

*Quantum information: lectures notes*,

2021, unpublished.

2. S. Aaronson,

*Introduction to quantum information science: lecture notes*,

2018, unpublished.